The original intention of Residential Schools was to assimilate Aboriginal peoples; their languages, cultures, and lifestyles were to be made to resemble those of Euro-Canadians. The Canadian government wanted to effectively “kill the Indian in the child,” a statement that makes clear the violence inherent in their attempts to integrate indigenous peoples into their version of society. It is doubtful, however, that these attempts at assimilation were ever truly intended to elevate First Nations Canadians to a position equivalent to that of Euro-Canadians. As Homi Bhabha explains in Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse,

Colonial mimicry is the desire for a reformed, recognizable Other, as a subject of a difference that is almost the same, but not quite (Bhabha 3)

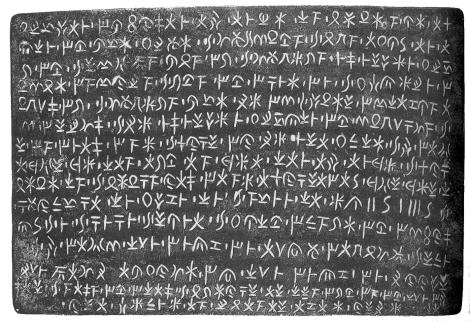

Indigenous cultures were, and often still are, seen as posing a threat to the dominant North American culture. The Residential Schools were designed to make them blend in more easily, but the logic inherent to such a system would never allow for them to be the same. Even current discussions like those of the National Post that consistently refer to Canada’s First Nations peoples as pre-historic and Palaeolithic betray the underlying and implicit assumption that they will always be backwards. After all, how could they ever be expected to catch up if they are already centuries behind? If Western discourses on progress and civilization are to be believed, a group who starts so far back on an upward moving timeline can have little hope of being equal to those who are allegedly reaching the pinnacle. Lucius Outlaw discusses this in his essay Toward a Critical Theory of Race, in which he highlights some of the issues associated with assimilation. Outlaw writes “the socially devisive effects of ‘ethnic’ differences were to disappear in the social-cultural ‘melting pot’ through assimilation, or, according to the pluralists, ethnic identity would be maintained across time but would be mediated by principles of the body politic” (Outlaw 61).

Because the construct of race is already so heavily ingrained in different facets of society, and understandings of race are largely hinged upon visible differences, even the most successful attempts at mimicry could never eliminate the stigma associated with indigeneity. As Outlaw explains, “the state is inherently racial, every state institution is a racial institution, and the entire social order is equilibrated (unstably) by the state to preserve the prevailing social order” (Outlaw 80-1). The Residential Schools legacy, as well as the articles from the National Post, assert that Western knowledge is superior to indigenous knowledge, and thereby place Native Canadians lower down on an ‘evolutionary’ scale.

Robson betrays this prevailing belief in the good of assimilation when he quotes Thomas Sowell, who disparages “prevailing doctrines about ‘celebrating’ and preserving cultural differences,” asserting that “cultures are not museum pieces” (Robson 8). Conrad Black, on the other hand, flat out states that “[Europeans] have made vastly more of this continent than its original inhabitants could have done” (Black 11). It would seem that, if they could just adhere to European ideals and beliefs, the indigenous peoples could become one with the dominant Canadian culture and thrive “on the basis of demonstrated achievement” (Outlaw 61). This ability to demonstrate progress, that is typically measured by Euro-Americans in terms of economic development and scientific rationality, has been frequently used to differentiate between the ‘civilized’ and the ‘uncivilized’. All of this ignores, however, the previously mentioned issue of visible difference. If racism was not so heavily institutionalized this argument could have more weight. But, as Bhabha states, the colonizer, in attempting to create a likeness of themselves but still maintain that slippery difference, will focus on the obvious signs of mimicry. The colonized will continue to be “Almost the same but not white” (Bhabha 12). This ultimately provides evidence of the power of the discourses discussed in previous posts on this blog. These ways of understanding the world, for which the National Post and the Residential Schools have both served as relays, equate civilization with progress. They measure progress in terms of the value of a group’s knowledge and therefore their access to truth, meaning that civilization can only be granted to othered groups who manage to adhere to ‘western’ ways. As Bhabha has already noted, however, their inability to ever become truly the same (and the underlying desire of a colonizer to maintain that slippery difference between the ‘other’ and themselves) reinforces the dominant group’s use of race as a proxy for civilization.

This ultimately provides evidence of the power of the discourses discussed in previous posts on this blog. These ways of understanding the world, for which the National Post and the Residential Schools have both served as relays, equate civilization with progress. They measure progress in terms of the value of a group’s knowledge and therefore their access to truth, meaning that civilization can only be granted to othered groups who manage to adhere to ‘western’ ways. As Bhabha has already noted, however, their inability to ever become truly the same (and the underlying desire of a colonizer to maintain that slippery difference between the ‘other’ and themselves) reinforces the dominant group’s use of race as a proxy for civilization.

Despite its inability to create an equal relationship between the ‘colonizer’ and ‘colonized’, mimicry does have the ability to be subverted. The group that has been subordinated has the power to turn mimicry into mockery, and to effectively gaze back at their colonizers. One of the ways in which this subversive power can be exercised is through literature, like Sherman Alexie’s poem How to Write the Great American Indian Novel. In it, Alexie is able to critique the history of fictitious representations of indigenous identity in literature. He mocks a series of literary tropes that consistently reinforce a narrative where the Native people must disappear in order to make room for the white people. In doing so, especially as he presents it in the form of a rulebook, Alexie sends up the literature that has been an instrument of domination for Empire, explaining that when this great American Indian novel is written, “all of the white people will be Indians and all of the Indians will be ghosts” (Alexie 40).

the human evolutionary path?

the human evolutionary path?